Music History Fact Of The Week: Charlie Bird Parker

Music History Fact Of The Week: W.C. Handy

W.C. Handy is known as “The Father of the Blues.”

W.C. Handy is known as “The Father of the Blues.”

When he had a problem getting his artistic works published, he became a self-sustaining business man and published his own works.

According to wikipedia, in 1917, Mr. Handy moved his business to New York City. His office was located in a building in the Times Square area.

The History Behind The Song, “Self-Destruction”

“Carli, one of the leading rap record executives, and George, now the Black music editor for Billboard magazine, decided to make an all-star rap record and donate the profits to charity. They called their project the ‘Stop the Violence Movement,’ after a Boogie Down Productions’ song. Carli asked Boogie Down Productions’ youngest member, Derrick ‘D-Nice’ Jones, to produce the track. Both she and George enlisted the help of the most popular rappers in the genre: Chuck D and Flavor Flav from Public Enemy, KRS-One and Kool Moe Dee, Heavy D, the members of Stetsasonic. The young prince of rap, LL Cool J, still smarting from his battle with Kool Moe Dee, was the lone holdout; but he helped a female rapper named MC Lyte write her verse. Ann Carli’s own artists, DJ Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince begged to be included, but Carli felt that their image was too ‘soft’ for the project, and might detract from the record’s credibility with the ‘hard rocks’ they were trying to reach.

Recruiting the rappers for the project turned out to be easier than securing a record deal, even with the star-studded cast. Russell Simmon’s Def Jam and Andre Harrell’s Uptown Records passed on the project, because the executives didn’t think they could make any money on it. Tom Silverman very much wanted the record for Tommy Boy, but Carli was turned off when Silverman explained to her how they could donate all the artist royalties to charity, while keeping the profits from the record’s distribution for themselves- just like EMI had done with another charity record called ‘Sun City.’

In the end, Carli came home to Barry Weiss and Clive Calder at Jive, who agreed to donate everything but the cost of the project to the National Urban League, for programs combating Black-on-Black violence.

The video for the song, ‘Self Destruction,’ was the largest-ever gathering of rappers on one record, uniting the biggest names in hip-hop for the common good. In the video, KRS-One rapped to his colleagues from a podium at Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, blaming the ‘one or two suckas, ignorant brothers’ for the violence, not the rap audience. While Kool Moe Dee contributed one of the most memorable phrases (‘I never ever ran from the Ku Klux Klan,/and I shouldn’t have to run from a Black man’), the video featured other extraordinary moments, including the sight of former adversaries Red Alert and Marley Marl standing beside each other in a cemetery, over a plot that few but insiders knew was the final resting place of DJ Scott La Rock.

The video, released in the late winner of 1989, was carried to televisions across the country by Yo! MTV Raps, and sold enough records to raise $500,000 for the National Urban League.

The Stop the Violence Movement was largely New York’s response to a local incident. Tone-Loc was the only out-of-towner to make a cameo in the video. But Tone-Loc participated in California’s answer to ‘Self Destruction’ the following year, when he, Young MC, Ice-T, MC Hammer, Digital Underground, NWA, and others joined forces to create the West Coast All Stars, and their antiviolence song, ‘We’re All in the Same Gang.’” -From, “The Big Payback” By: Dan Charnas

Guns & Drums: The Power Of The Drum

“It was the slaves’ day off. About twenty of them of things rolling on Sunday, September 9, 1739, breaking into a warehouse less than twenty miles south of Charlestown, South Carolina, grabbing guns and powder, and shooting sentries that got in their way. They were African born, with memories of life in the Kingdom of Kongo (modern Angola, Cabinda, and the Republic of the Congo). Many were former Angolan soldiers. Now they were soldiers once more.

“It was the slaves’ day off. About twenty of them of things rolling on Sunday, September 9, 1739, breaking into a warehouse less than twenty miles south of Charlestown, South Carolina, grabbing guns and powder, and shooting sentries that got in their way. They were African born, with memories of life in the Kingdom of Kongo (modern Angola, Cabinda, and the Republic of the Congo). Many were former Angolan soldiers. Now they were soldiers once more.

They marched from the Stono River heading south for Spanish Florida, where other escaped slaves had been granted freedom. Along the way they gathered guns and drums. The cadence they beat on those drums drew more to their ranks, as did their songs and the banners they carried. They shot whites as they found them, spared a tavern owner who had been good to his slaves, and burned plantations. The rebels could not, however, kill all of their tormentors. The lieutenant governor escaped their onslaught and returned with a brigade of planters and militiamen. Outnumbered and having lost the element of surprise, the rebels were defeated by the following Sunday. More than forty blacks and 20 whites were killed in what was called the Stono Rebellion. Stono was the largest slave revolt to shock the colonies in the eighteenth century.

After it was over, the governor of colonial Georgia, expressing his concern over the insurrection next door, filed a formal report to a representative of the Crown:

‘On the 9th day of September last being Sunday which is the day the Planters allow them to work for themselves, some Angola Negroes assembled, to the number of twenty…Several Negroes joined them, they calling out liberty, marched on with colors displayed, and two drums beating, pursuing all the white people they met with, and killing man woman and child…They increased every minute by new Negroes coming to them, so that they were above sixty, some say a hundred, on which they halted in a field, and set to dancing, singing, and beating drums, to draw more Negroes to them, thinking they were now victorious over the whole Province, having marched ten miles & burnt all before them without opposition…’

Dancing, singing and beating drums: a unity expressed in performance. The drums communicated beyond the reach of the voice, and beyond sight. They moved bodies to join in brotherhood.

After the Stono Rebellion, South Carolina stopped importing African-born slaves. Too unmanageable. This hiatus lasted ten years, and when the colony again ventured into ttrade, it avoided slaves from the Congo-Angolan region. Colonial legislators frantically passed the Slave Code of 1740, banning chattel from using or even owning drums. The overall law forbade drums and swords alike, making clear how South Carolina viewed the instrument: as a weapon.

That was how white colonials valued the drum. They had their own tradition of military percussion, and drawing on it, they understood the slave music as a call to war.

But to black Carolinians, the rhythms of Stono meant war and more. Drumming was a way of representing yourself as an imposing force, a way of demanding respect. As historian Richard Cullen Rath puts it, ‘The [Congolese] court tradition, which manifested itself in the drumming and dancing that so intimidated planters, was a means of directly representing and displaying power…[It was] perhaps the original form of broadcasting.’

South Carolina’s ban on drums stayed on the books for over a century, all the way to the Emancipation Proclamation. But, failing to understand the African use of the instrument, the colonial legislature achieved a meaningless goal. The cadence continued by alternate means. One legacy of the Slave Code was the bondsmen found other ways to keep rhythms alive without a drum: Writers of the time record a skill amongst slaves for tapping with different parts of their bodies, hitting the floor and wall with sticks, clicking, banging, and most of all, dancing. That patting, tapping, dancing all flowed into the body as surely as it flowed from it; it was absorbed and passed on to new arrivals. There was a kind of underground flowering after 1740, a sharing of skills that made the drum unnecessary at the same time that it made drumming ubiquitous. Rhythm created community. It brought the news.” -From, “The One: The Life and Music of James Brown” By: RJ Smith

[SIDEBAR: Guns & Drum is a hot name for an album or a song!!]

One Of The First Recorded Rap Records: Rhymin’ and Rappin’

The Creation Of Black Radio in NY and What WBLS Really Stands For

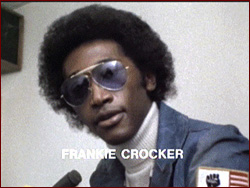

“In 1971, a Harlem lawyer and politician named Percy Sutton led a group of Black investors, including David Dinkins, to buy two New York stations, WLIB-AM and FM. Sutton Changed the FM station’s call letters to WBLS, and hired Frankie Crocker as his star air personality and first program director.

“In 1971, a Harlem lawyer and politician named Percy Sutton led a group of Black investors, including David Dinkins, to buy two New York stations, WLIB-AM and FM. Sutton Changed the FM station’s call letters to WBLS, and hired Frankie Crocker as his star air personality and first program director.

The call letters ‘BLS’ were said to stand for ‘Black Liberation Station.’ Indeed, WBLS gave Frankie Crocker freedom during a time of corporate captivity for Black music and Black artists. In turn, Crocker’s WBLS freed the minds of a generation of New Yorkers. Under Crocker, WBLS redefined and expanded the concept of the ‘Black’ radio station. To the traditional soul and R & B fare of James Brown, Aretha Franklin, and Stevie Wonder, Crocker added an eclectic mix of rock, jazz, and pop standards- everything from Rolling Stones to Frank Sinatra. Crocker’s tastes were broad and cosmopolitan, and he expected no less from his listeners. He gave New Yorkers their first taste of a Jamaican rock-and-roller named Bob Marley. Crocker was among the first on the radio to play the beat-heavy, dance-oriented, soul that was becoming so popular in the new DJ-driven nightclubs called ‘discotheques,’ records like Manu Dibango’s ‘Soul Makossa’ and MFSB’s ‘Love Is The Message.’ Crocker presented a show that was sophisticated and grown-up. If WWRL was Harlem, WBLS was Sugar Hill- a cut above, a station that gave its listeners a taste of upward mobility…

In a time when Black music was being pushed from the airwaves across the country, and record and radio executives subscribed increasingly to the notion that there were records that were simply ‘too Black’ for White listeners, Frankie Crocker turned WBLS into the number one-rated music station among all listeners in the largest city in the country.

More profoundly, Crocker created a generation of young music aficionados in New York, kids from the inner city and from the suburbs, to whom he gave the gift of an open mind and the notion that a DJ could change the world.” -From, “The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop” By: Dan Charnas

Dionne Warwick Talks About Sam Cooke Part 2

“Sam Cooke was a real cutie. He was a kind, gentle, and caring man who always had something nice to say to and about people. When I learned that Sam was having a party in his hotel suite one evening, I knocked on his door. When he saw it was me, he said, ‘I know your mother, and you can’t come in here.’ He then walked me back to my room. I was upset at being excluded, but I knew that Sam meant well; he was very protective of me, like a father. I first met him on the gospel circuit while he was with the Soul Stirrers, whom the Drinkards would occasionally tour with. I loved being around him because he always had a smile on his face and was always humming either one of the gospel songs he used to sing or someone else’s song that he loved…

“Sam Cooke was a real cutie. He was a kind, gentle, and caring man who always had something nice to say to and about people. When I learned that Sam was having a party in his hotel suite one evening, I knocked on his door. When he saw it was me, he said, ‘I know your mother, and you can’t come in here.’ He then walked me back to my room. I was upset at being excluded, but I knew that Sam meant well; he was very protective of me, like a father. I first met him on the gospel circuit while he was with the Soul Stirrers, whom the Drinkards would occasionally tour with. I loved being around him because he always had a smile on his face and was always humming either one of the gospel songs he used to sing or someone else’s song that he loved…

Sam was also a smart man who saw the importance of owning his songs. He took steps to copyright and publish them himself and owned his catalog- an unusual thing for an artist during this time in the music industry. Most would sell their writing rights to a publishing company.

The news of his death on December 11, 1964, a day before my twenty-fourth birthday, was devastating. I was going to Los Angeles for the first time, at his expense, to celebrate my birthday with him and some friends.” -From, “My Life, As I See It” By: Dionne Warwick

Dionne Warwick Talks About Sam Cooke Part 1

“Our tour bus was parked at the stage of the coliseum right by a little restaurant called the Toodle House. Sam asked us to go and get all of us something to eat. La La Brooks, the lead singer of the Crystals, wrote down what everybody on the bus wanted, then we went into the restaurant to get the sandwiches. There happened to be only two other people in the restaurant, and they were sitting in a booth. So La La and I sat at the counter, where we noticed a handsome African American man was the cook.

“Our tour bus was parked at the stage of the coliseum right by a little restaurant called the Toodle House. Sam asked us to go and get all of us something to eat. La La Brooks, the lead singer of the Crystals, wrote down what everybody on the bus wanted, then we went into the restaurant to get the sandwiches. There happened to be only two other people in the restaurant, and they were sitting in a booth. So La La and I sat at the counter, where we noticed a handsome African American man was the cook.

Well, this white waitress came rushing over, ordering us to get up for the counter. We thought she had lost her mind and quickly stood up. She ordered us to go to an area off to the side. When we got to where she told us to go, we figured that this was where she took her breaks because there was an ashtray with cigarette butts, a half cup of coffee, and a couple of aprons hanging on the wall. With that, I asked, ‘Can we get a menu?’ The waitress snapped, ‘You will just shut up and wait until I get to you.’

Being all of twenty-three years old and not used to being yelled at- especially by someone like this woman- I responded, ‘Hell no, we won’t wait, and you can take the menus and shove them as far up your butt as you can get them!’ La La and I then left and got back on the bus.

Less than five minutes later, a sheriff’s car came to a screeching halt at the front of the bus. An officer stepped onto the bus demanding to see the two ‘colored girls’ who were just in the Toodle House. Sam Cooke said to the officer, ‘There are no ‘girls’ on this bus, just young ladies. And what do you want with them?’

The officer said that the two young ladies had insulted the waitress, and he wanted them to apologize to her. Sam laughingly but politely asked the officer to leave the bus since it was private property and he had not been invited on. The unspoken message was that no one on the bus would be giving an apology to anyone. The officer left in a huff. Sam said to La La and me, ‘I should have let him have you two. Just think of all the publicity we would have gotten for this tour.’ The bus rocked with laughter.” -From, “My Life, As I See It” By: Dionne Warwick